With “Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery,” writer-director Rian Johnson gave himself a series of challenges — a murder mystery that’s emotionally involving, fast-paced and witty, with socio-political themes. Against huge odds, he makes it work.

The story centers on a billionaire (Edward Norton) who sends invitations to five frenemies for a murder-mystery game on his Greek island. Also attending is the world’s most famous detective, Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig).

Don’t worry, there are no spoilers here.

“Anyone who’s made a movie knows the hardest thing is the introduction,” says Johnson. “I thought a lot about the first 10 minutes: How can I give the audience all the information they need — including this huge ensemble of characters, the promise of a murder mystery — how can I do that, in an entertaining way, where it doesn’t feel like work for the audience?

“That required a lot of engineering, structuring the whole thing around the game of opening the box.” The sequence showcases the deft touch of editor Bob Ducsay and the writer-director.

Another showcase for the director and editor occurs just before dinner on the first night; all the principals are gathered in a room, with tensions rising.

“That sequence was very complicated,” Johnson says. “The hardest part was shooting it: You have seven or eight people onscreen. I wanted to have multiple people in the frame; I didn’t want to do just singles on everyone. And because of the nature of the sequence, there are moments where I want the audience’s eye to be someplace, or to NOT be someplace. There was a lot of ‘math’ in planning the blocking and shooting.”

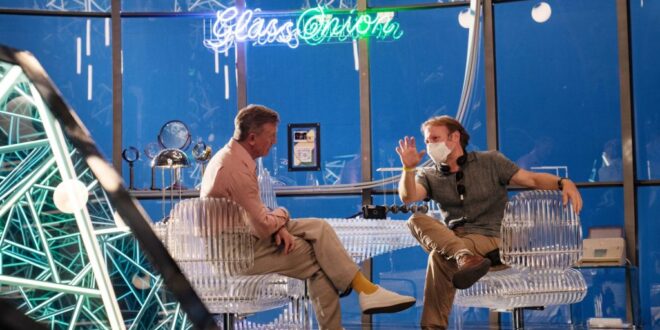

That’s one of many key scenes that take place in the house’s huge atrium and Johnson pays tribute to production designer Rick Heinrichs. “With something that feels fun like this, it’s easy to overlook the artistry and the amount of work.

“The atrium space is basically three sets in one. With each of three big setpieces, we move to a different space: the vibrant red of the seating area, the austere black and crystal of the Mona Lisa space, and then the bizarro Greek-ruins section where the dining table is. Rick wanted it to feel slightly tacky because they don’t belong together but also to merge together, so your eyes don’t throw up. It’s kind of extraordinary what he did.”

Cinematographer Steve Yedlin offers tour-de-force work when the lights go out; the audience sees shadowy figures moving in dark spaces, occasionally interrupted by harsh beams from a lighthouse.

“Steve has posted on his website about the rig he created, to create the lighthouse effect. It’s this crazy, specifically timed computer-based drum rig. But it had to be timed exactly right; the light was so bright we had five seconds to get the shot or it would catch on fire..”

Finally, the writer-director salutes the film’s composer. “Nathan Johnson is my cousin; we’ve been making movies since we were 10. His references were the big, lush, orchestral movie-movie scores; we wanted something unabashedly romantic, grand and mysterious. But it’s not just the big moments; he also sculpts the music with nuance, so it is almost invisible; that to me is the real magic of what he does. Without you noticing it, he’s elevating every emotion in the scene.”

“I’ve been lucky enough to direct my own scripts,” says Johnson. “There are different stages of moviemaking but essentially it’s one long process. I’m thinking with an editor’s brain when I begin writing and even when I’m in post, I feel like I’m still writing.”

Ducsay’s editing savvy was also crucial for the tone and rhythm of a comedy with a lot of plot twists.

“The pacing with any film is crucial and this in particular was a delicate balance,” Johnson says. “The answer is not always to speed up; that can leave the audience exhausted. This is not a new thought, but the audience needs moments to breathe while the plot is constantly moving forward.

“Halfway through the film we have a 10-minute scene that’s Blanc and another character sitting at a table talking; it’s moving the story forward, with rapid shifts in perspective. The usual instinct would be to hit the gas and accelerate. But we didn’t; the audience will sit for it because they understand why they’re sitting for it.

“For that scene, it was a matter of me figuring out where the act breaks are, and we played it out in long chunks. If you watch the scene, you’ll see where I give line breaks with the camera; it gives the audience a fresh view of the scene.”

Johnson also praises the actors and editor Ducsay for maintaining the movie’s breezy-but-deadly-serious tone.

“On Day One, you have to dial it in fairly quick. It’s a true ensemble piece. We intentionally scheduled everyone’s arrival on the dock as the very first scene we shot. That meant all these great actors could listen to each other, gauge each other’s levels and we could dial it in as a unit on that first day. Even when you have it dialed in, you’re still throwing darts from a moving car during production. A big part of the tone comes together in the edit; then it’s Bob and I trusting our guts, honing a line reading or reaction.”